oil on canvas

100 x 150 cm

2013

oil on canvas

70 x 50 cm

oil on canvas

90 x 60 cm

2017

oil on canvas

70 x 50 cm

2013

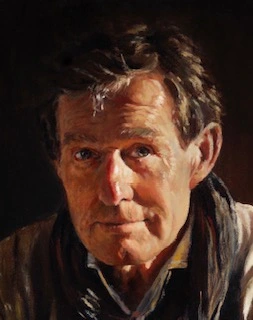

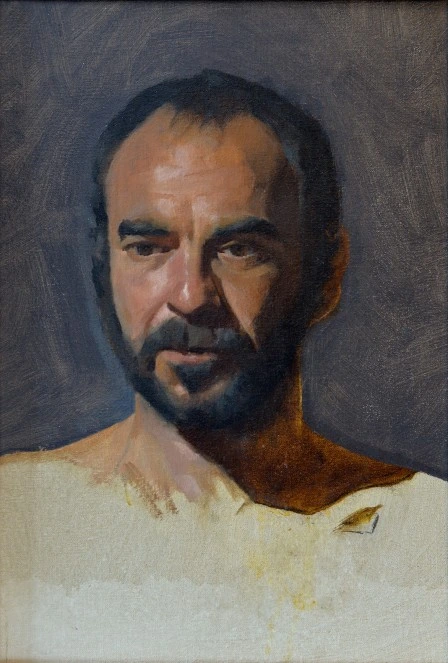

oil on canvas

40 x 50 cm

2016

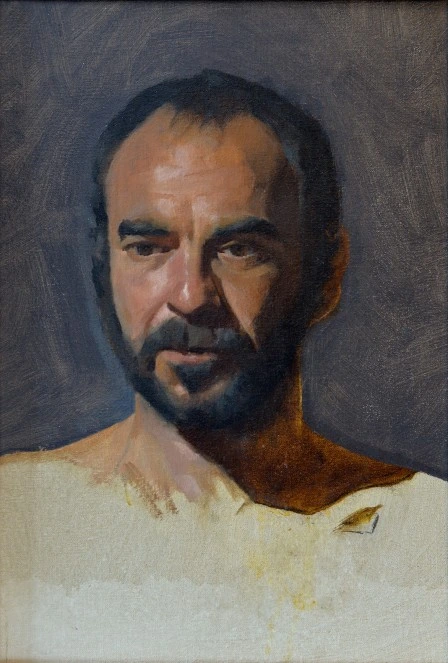

oil on canvas

32 x 22 cm

2011

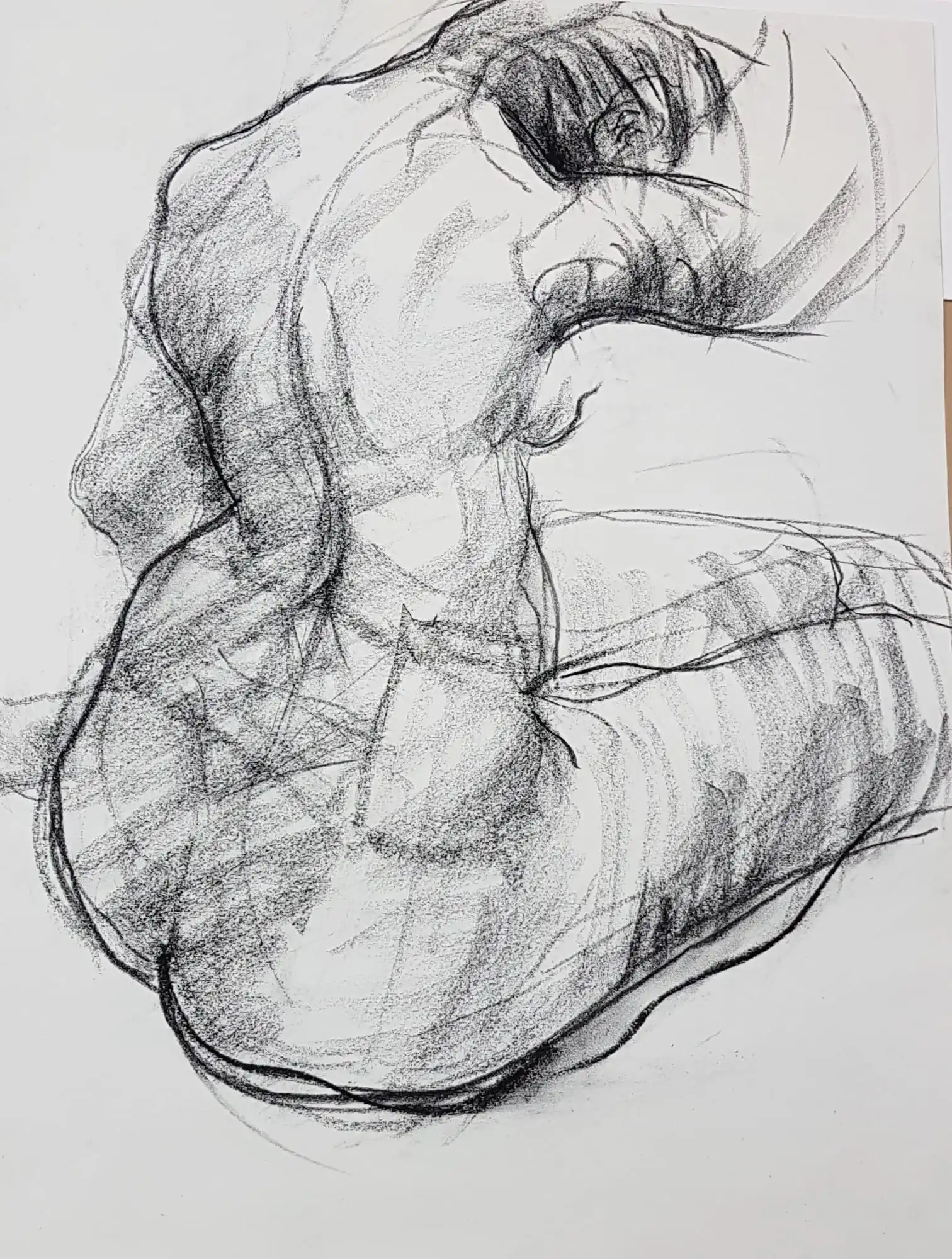

charcoal on paper

100 x 70 cm

2016

oil on canvas

30 x 40 cm

2021

charcoal and pencil on paper

244 x 122 cm

2013

oil on canvas

70 x 50 cm

2021

oil on canvas

90 x 60 cm

2015

oil on canvas

50 x 70 cm

2020

oil on canvas

50 x 70 cm

2013

wax

2018

oil on canvas

70 x 50 cm

2013

oil on canvas

70 x 50 cm

2013

black and white pastel on paper

15 x 10 cm

2011

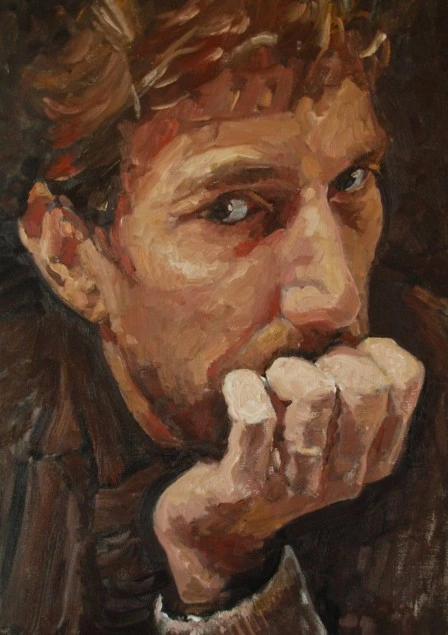

oil on canvas

70 x 50 cm

2013

oil on canvas

40 x 30 cm

2014

charcoal on paper

70 x 50 cm

2018

Wim Bakker

Painting is a late vocation for Wim Bakker (Marsum 1969). After a successful career in business and top sport, the passion for painting came as a surprise. With the same drive with which he had shaped his previous career, new steps were taken to master this unknown field. Perhaps the confrontation with the work of Sam Drukker was the real reason for making the switch to being an artist, so the decision was made to study at the Wackers Academy in the first place.

After this thorough introduction, Bakker opted for a foreign follow-up with masterclasses in Spain, Italy and Sweden. In the space of a few years, drawing and painting has become second nature to him. With the eye of an analyst, his subjects are studied down to the smallest detail and then integrated into a larger composition. There is little room for chance in his paintings. However, the sketchbooks betray that there is almost always a moment of spontaneity in which the first thoughts and feelings are committed to paper. The drawing from a model and the notes made of the great classical examples while sketching ensure that the artist is well aware of the place he occupies in the tradition. That same consciousness then gives the freedom to shape one's own.

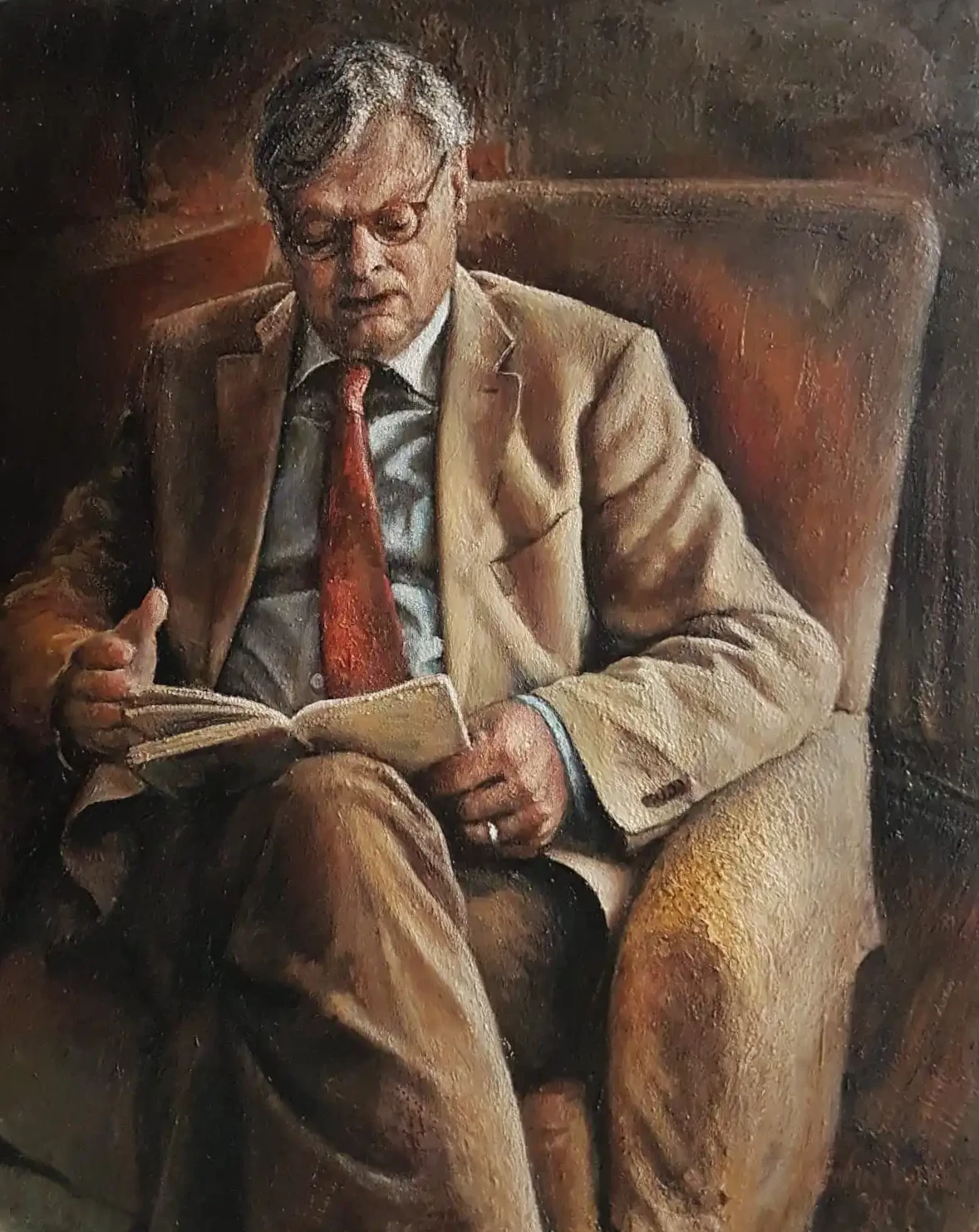

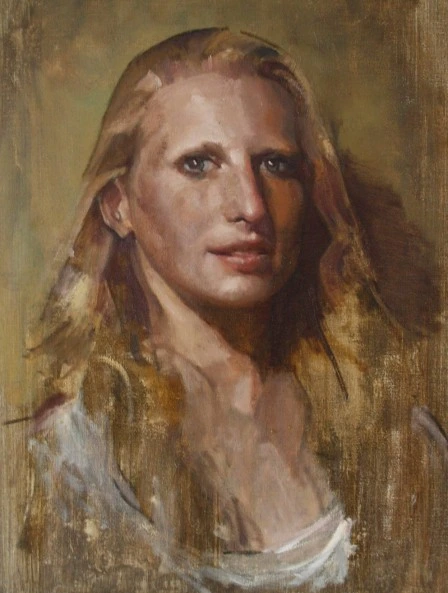

Portraits

The portrait is one of the great subjects in art history. It has an enormous variety in the most diverse forms. We only have to look at the painted and drawn portraits in the Western tradition to realize that it is a big job to get a reasonable overview.

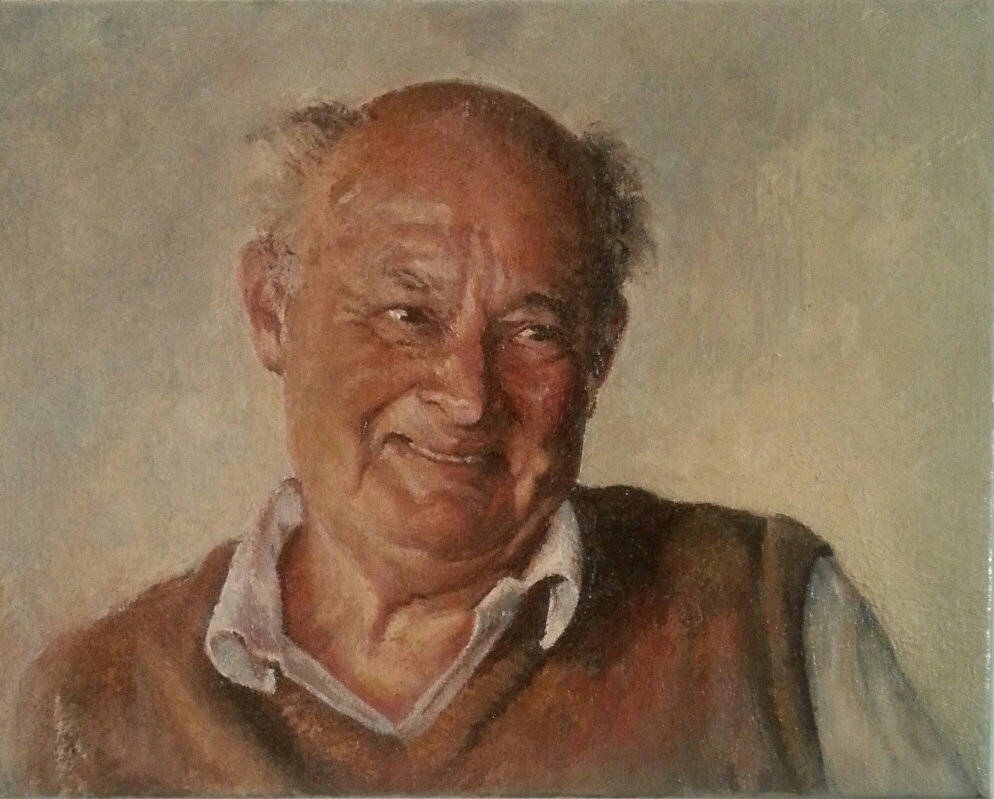

Portraits occupy an important place in Wim Bakker's oeuvre, placing him directly in that long line of artists who preceded him in making similar images of people. Such a choice also entails a certain risk. Not only are there the great masters you will be compared to, but there is also the inexorable possibility of comparing the painted result with, say, a photographic truth. A true-to-life resemblance between the person portrayed and the portrait often seems to have become a requirement of the client and the public. Such a thing is a pity, especially since there are more criteria to determine whether a portrait also 'works' as a work of art. A 'well' painted portrait is the result of, among other things, observation, interpretation and translation into material on a background. Unfortunately, the same also applies to a 'bad' portrait. It is good to realize, however, that we cannot verify an element such as 'similarity' in the somewhat older painted and sculpted portraits. The quality of great portraitists such as Frans Hals, Rembrandt and Isaac Israels is that they know how to convince. They present a person who has become a painted reality for us, thereby exceeding the illusion of the painting. Striving for such a high standard is a challenge and, in addition to talent and technique, also requires a fair dose of guts. The higher the bar, the harder the criticism and then mediocrity is no longer an option.

Critical look

Wim Bakker has not been put off by either the big names or the obvious comparison. His sketchbooks reveal that he studied the classical examples with great fascination. Small virtuoso sketches show a cross-section of the collections he has visited and occasionally a milestone like Velazquez' pensive Mars, in a reduced version, ends up on a panel. The will to become as good as this characterizes the mentality of the artist. The aspiration is to reach the top and failure is less bad than not trying… and no one is more critical than the artist himself.

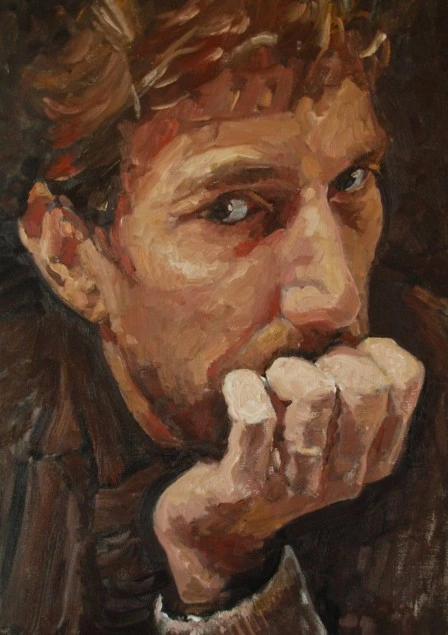

This critical view of his own work is clearly present in the self-portraits. The small series, whether fragmentary or not, of self-portraits not only shows how high the technical requirements are, but also shows the merciless look on one's own face. Close to the mirror and close to the skin, a world is created in which nothing escapes the eye. Very precise observation and recording come together on a few square centimeters. You could just end up in the world of miniature painting, but the wonderful thing is that there is rather a sensation of monumentality. Self-portraits usually tell the most about an artist, while the artist often wants to say the least about those self-portraits. Talking in the studio with Wim Bakker, the stories about the (portrait) models come loose quite easily. They provide a colorful picture of the daily practice of the portraitist and could easily be written down in the context of another book. It is different with the self-portraits. The conversation is about technique or about satisfaction with the result, but rarely about recognition. It is not until the somewhat larger painting on canvas that Bakker pauses and raises his fist to his mouth in the characteristic pose. “I only realized that after painting this self-portrait,” he says, “that I often look like that”. Observation and interpretation are already anticipating, perhaps to the next self-portrait.